KANSAS CITY — Transportation capacity and costs have somewhat normalized since the unprecedented challenges during the height of COVID from 2020-22, but the dynamic industry continues to experience fluctuations and challenges, especially when drilling down to specific sectors like agriculture, or even more specifically to grains. The broad view is increased truck and ocean freight capacity has been favorable for shippers in driving down freight rates while rail rates have varied. Rising fuel prices, which generally are passed on to shippers, have added to shipping costs across all transportation modes.

Barge traffic, and subsequently US grain and soybean exports, are being challenged by low water levels on the lower Mississippi River. Panamax ocean-going vessels, meanwhile, are facing low water levels through the Panama Canal. Railroads are performing well, but forecasts of a hard winter could bring challenges in the months ahead.

On a broad scale, the September Logistics Managers’ Index (LMI) released in early October was 52.4, up from 51.2 in August and compared with 61.4 in October 2022. It was the second consecutive monthly increase after declining for six consecutive months (five of which were new lows) to an all-time low of 45.4 in July and indicated the strongest growth in the logistics sector in seven months. The highest index of 76.2 was posted in March 2022. The September index was the highest since February, with the increase “fueled by continued growth in the warehousing market, increased inventory costs, and some signs of green shoots emerging in the transportation industry,” according to index researchers.

“This second consecutive expansion provides further evidence suggesting that the move toward growth in August was not a one-off occurrence and may have marked a turning point back toward growth in the logistics industry,” LMI researchers said.

“This second consecutive expansion provides further evidence suggesting that the move toward growth in August was not a one-off occurrence and may have marked a turning point back toward growth in the logistics industry,” LMI researchers said.

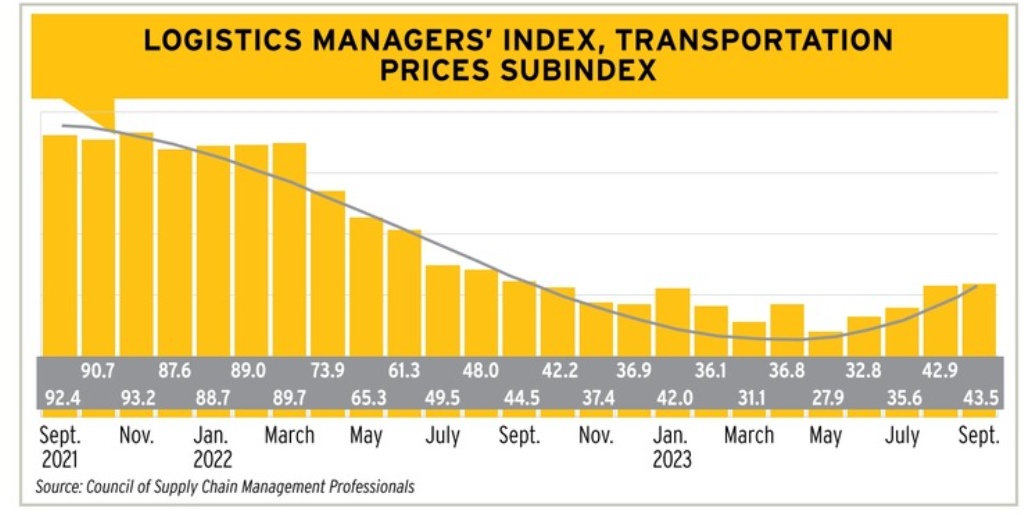

The transportation capacity component of the LMI at 64.3 in September broke a three-month downturn but still was well below 71.8 a year ago. The transportation utilization index was 53.5, up for the third consecutive month but still below 61.1 in September 2022. The transportation price index of 53.5 rose for the fourth consecutive month from a low of 27.9 in May and compared with 44.5 a year earlier.

“The downward pressure on transportation prices eased a little more, but the index remains slightly in contraction territory,” index researchers said, noting higher transportation prices were expected over the next year.

The LMI is a combination of eight unique logistics components, including inventory levels and costs, warehousing capacity, utilization and prices, and transportation capacity, utilization and prices. The index was started in 2016 and includes input from researchers at five universities in conjunction with the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals. An index reading above 50 indicates logistics are expanding, and a reading below 50 indicates the industry is shrinking based on a diffusion index used to analyze raw data collected from the LMI panel.

Prices of another major cost component — diesel fuel — have been moving higher since June but remain below year-ago levels. Retail on-highway average diesel fuel prices from the Energy Information Administration of the US Department of Energy have reflected recent gains in crude oil prices that have moved modestly above year-ago levels. The US average diesel price for the week ended Oct. 9 was $4.50 per gallon, up 15% from the summer low but down 14% from a year ago. Fuel surcharges added to truck and rail freight rates have moved in step with the on-highway average price. Ocean freight owners have additional fuel concerns because of recent and planned requirements to reduce carbon emissions that are expected to result in higher freight rates, slower transit times and port restrictions for certain vessels that don’t meet the higher carbon emissions standards.

Demand for grain transportation, which can create strain on various modes of shipping, has been down due to smaller total crop production in 2022. Total grains inspected for export for the various crop marketing years as of Oct. 5 were down 13% from the same time last year, with wheat exports in the first four months of its marketing year running 30% below a year earlier but corn and soybeans in just the first month of their marketing years running a combined 11% ahead. Rail car loadings of grain for the calendar year through Sept. 30 were down 13% from the same period a year ago, according to the Association of American Railroads. That could change, though, in the year ahead as the USDA estimated 2023 wheat production up 10% from 2022 and forecast corn production also up 10%, more than offsetting a 3% drop in soybean production.

Barge movement hampered

Drought once again has played a role in access to domestic export channels via inland waterways. The lack of rain has caused the Mississippi River to drop to abnormally low levels resulting in a buildup of barge traffic ahead of the crucial period of fall row crop harvests.

It is an unfortunate case of déjà vu for the waters of the Delta region. Last year, barge freight rates on the Mississippi River soared to record highs as drought-diminished river levels limited barge movement. Data from the US Department of Agriculture’s ag transport barge dashboard indicated it cost 202% more in downbound grain barge rates to move 57% less grain in the week ended Sept. 24, 2022, than it did at the same time in 2020. The situation this year is concerning but so far not as severe. The USDA said it still costs 134% more in downbound grain barge rates to move 26% less grain in the week ended Sept. 30 compared to the same period in 2020.

While not yet as dire as 2022, the depressed water levels this year are still a serious problem, especially at the river’s mouth where salt water from the Gulf of Mexico was starting to backflow up into the river and was threatening drinking water reservoirs. And while barge traffic on the river has become more congested, the reduction in grain exports compared with 2022 has helped offset some of the bottlenecking, though barged grain movement was expected to increase as the corn and soybean harvests progress.

According to its Oct. 5 Grain Transportation Report, the USDA said downbound barged grain volumes on the Mississippi River were 25% lower compared with last year and nearly 30% lower than the five-year average. The Department attributed the volume reduction to both slow export sales as well as the river’s dropping water levels, which became an issue in June, two months earlier than in 2022. The USDA said the Mississippi River levels were nearly two feet lower in some sections than they were last year, but other areas were higher.

Barges traditionally are ideal vessels for shipping large amounts of cargo. Fifteen barges bound together can transport about the same amount of cargo as approximately 1,000 trucks. Barges carry roughly 60% of all grain exported from the United States, and the Mississippi River is the direct route to the Gulf port region where 90% of US grain is exported.

To help maintain both river flow and barge transit, dredging operations have been undertaken at critical choke points along the river, but dredging is only a temporary solution until more rain raises water levels.

Restrictions on draft and tow sizes at various sections of the river system also have been implemented with the most stringent limits being set on the Lower Mississippi and Ohio rivers at Cairo, Ill., according to the USDA. But the Department indicated additional restrictions and higher barge rates were possible if the rivers do not receive sufficient rain soon.

“If low-water conditions in the (Mississippi River System) continue, lack of precipitation may lead to increased restrictions, which would further shrink an already tight barge supply,” the USDA said. “The rising harvest demand and shrinking barge supply may lead to above-average spot rates that approach last year’s record rates. However, lessons learned last year and early preventive measures may help mitigate conditions that created record-high spot rates seen in 2022.”

Ocean freight available

Ocean freight rates, both for bulk and container, are down sharply from record highs posted during the COVID period, and that isn’t expected to change significantly any time soon. China still is a key player determining the course of the ocean freight market, as it did during COVID.

“Ocean freight owners are crying in their soup,” said Jay O’Neil, HJ O’Neil Commodity Consulting, noting that current dry bulk rates are below those of 20 years ago in large part because China still hasn’t “come back” into the market. “We’re still waiting on the great China re-opening.”

Despite the decades-low rates, bulk freight rates have “started to wake up,” Mr. O’Neil said. Rates have increased slowly over the past three months, and they are “cautiously” expected to move higher in 2024. A positive for vessel owners is that they have not added to the fleet, Mr. O’Neil said. New vessel orders are only a net 2% of the fleet, which is historically low and will limit overcapacity during lower freight demand periods.

But the story is significantly different for containers. Compared with dry bulk carriers, the container market is vastly different as the result of ship owners’ reactions during COVID.

Container owners “shot themselves in the foot the last couple of years,” Mr. O’Neil said. High freight rates during COVID resulted in record-high profits for container owners. One way to avoid taxes was to build more ships, and container ship owners ordered 20% to 25% additional capacity. Since vessels take one to two years to build, that capacity just now is coming online as cargo demand is down and freight rates are at 20-year lows.

“We have a flood of new container ships coming online,” Mr. O’Neil said. “I’m not bullish on container prices inbound or outbound over the next 12 months.”

Railroads ready for harvest

Railroad performance typically is good coming out of the summer and heading into the fall row crop harvest period. Sharply higher corn and wheat production in 2023 may begin to stress rail capacity in the months ahead, in part depending on export shipments and certainly on winter weather.

The nation’s largest grain carrier — BNSF Railway — said it had worked to recover from one of the harshest winters in recent history and was ready for the fall harvest.

“Every year we collaborate with customers, plan and position our resources to execute a successful ramp-up for the busy fall harvest,” said Angela Caddell, BNSF group vice president of agricultural products.

The company added 50 locomotives to handle increased freight demand during the fall harvest and prepositioned more power in the northern United States while adding and prepositioning hopper cars.

The USDA in its Oct. 5 Grain Transportation report said average October shuttle secondary rail car bids and offers per car were $263 above tariff in the week ended Sept. 28, down $517 from a week earlier and down $1,483 from the same week last year. Average non-shuttle secondary rail car bids and offers per car were $275 above tariff, down $71 from the prior week but up $44 from a year ago.

Fuel surcharges in October ranged from a low of $86 per rail car for the route from Grand Forks, ND, to Duluth-Superior, Minn., to a high of $839 per car from Des Moines, Iowa, to Los Angeles.

Truck rates favor shippers

The trucking industry is experiencing the likely end of the COVID bullwhip effect.

Since COVID, carriers have fortified both their fleets and their staff through significantly enhanced sign-on bonuses, salary increases and expanded capacity. But now the industry feels saturated with capacity.

“It’s an interesting time because things are bouncing along the bottom from a demand and trucking standpoint,” said transportation analyst Jim Ritchie, president and CEO of RedStone Logistics, Olathe, Kan., and an instructor of supply chain management at the University of Kansas School of Business.

Mr. Ritchie said truckload prices are down overall, and spot prices are considerably lower than the contract market. In some cases, carriers were operating at a cost-per-mile level that was unsustainably below their operating costs.

The trucking industry is experiencing the likely end of the COVID bullwhip effect. Photo: ©TADA IMAGES – STOCK.ADOBE.COM

The trucking industry is experiencing the likely end of the COVID bullwhip effect. Photo: ©TADA IMAGES – STOCK.ADOBE.COM“We’ve had a lot of capacity enter the market just as COVID was starting to ease, so there were more trucks and more drivers and, all of a sudden, a whole bunch of capacity. But the demand never really bounced back in a big way, so now you have an excess of capacity, and everyone is competing against each other to try and figure out how to keep their assets moving, so they keep lowering their price to try and win the load,” Mr. Ritchie said, adding he worried some carriers were at risk for bankruptcy if they continued with this strategy.

But in recent weeks, the gap between spot and contract pricing appears to be closing as spot prices were incrementally moving higher while contract pricing was gradually declining. The situation may be a win-win for shippers, said Mr. Ritchie.

“If a carrier can’t survive, then ultimately you see capacity leave the market, and that will drive pricing considerably up, which is not necessarily good for shippers,” he said.

But finding a pricing balance was proving to be difficult with diesel fuel prices steadily rising, though still well below the record high of $5.81 per gallon set in June 2022. Ideas are diesel fuel prices are likely to sustain if not rise, especially with the recent conflict in the Middle East inserting more volatility into the crude oil market.

Also, many carriers are looking for a return on their investments after purchasing additional equipment, which was especially challenging for carriers servicing agricultural industries whose transit equipment is often specialized and not easily transferable to hauling other industry goods.

“When that demand drops, (agricultural) carriers really tend to suffer because where do they go to find additional capacity,” Mr. Ritchie said. “They’re in a niche. To be able to keep that asset moving is the goal of the carrier, and we do see prices dropping in that sector because if you’ve got a fixed cost to pay every month then you’ve got to keep your assets moving because some revenue is better than no revenue.”

Another supportive pricing element was the higher driver salaries, including higher rates carriers committed to paying during the pandemic.

“I was worried that some of that pricing component for the trucking carriers would remain high because once you raise salary rates, getting that back into line is always going to be a challenge,” Mr. Ritchie said. “But some of these incentives have been structured as certain incentive-based elements like signing bonuses, and now we’re starting to see it come down, but it’s still at a very high level.”

He added he thought a leveling in transportation labor costs was ultimately a good thing for both the trucking industry and shippers.

Overall, shippers are experiencing a mostly favorable period concerning ocean and truck freight rates, challenging barge freight rates and “as expected” rail rates that tend to systematically increase. Crop sizes, export demand, geopolitical events, energy values, weather and other factors will undoubtedly play a role in the ever-changing face of the transportation industry.